Diagnosing autism in infancy may have moved one step closer with ground-breaking research announced from Harvard University. A Ph.D. candidate, April Boin Choi has been investigating improved ways of identifying the development of autism in young children, particularly in children who have an older sibling with autism who are at higher risk of developing the disorder.

“Autism affects about one per cent of the population but for at-risk children, it jumps to 20 per cent,” Choi said. She believes the average age for detection of autism in children, around four years, is too late. “It means that those children may not have the access to resources and support that are especially critical during the earliest years of life.”

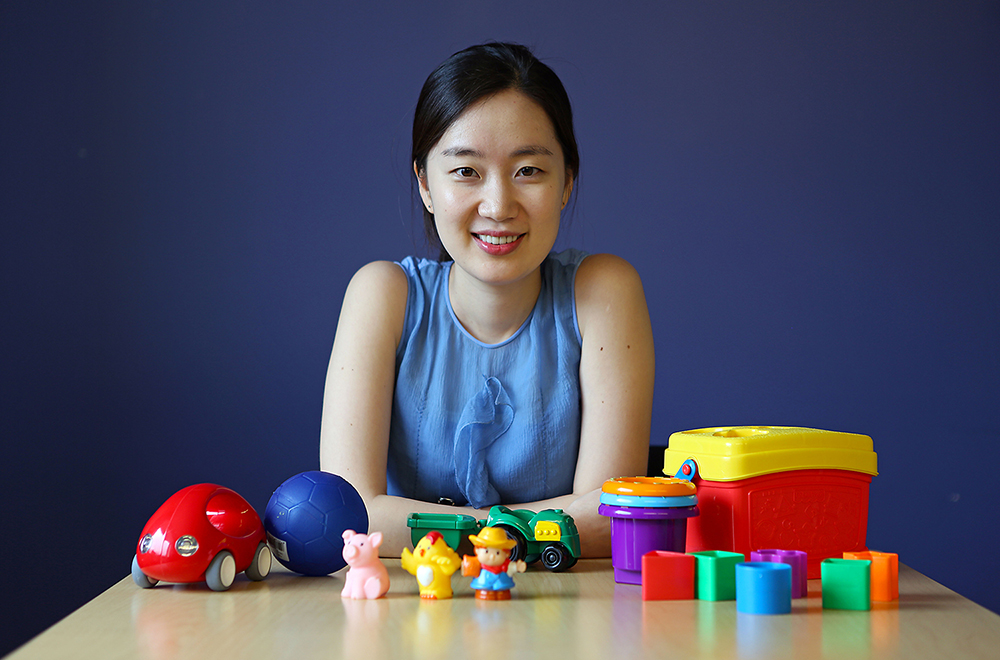

As a possible pathway to earlier diagnosis, Choi has been examining forms of communication, specifically hand gestures. Although researchers have long studied gesturing in preverbal children, less is known about gesturing in high-risk populations. Working at the Boston Children’s Hospital Lab of Cognitive Neuroscience with director, Professor Charles Nelson, Choi has been able to study a cohort of infants at high risk for developing autism.

“We found that high-risk infants produce fewer gestures, and that infants with fewer gestures at one year of age were later found to have more language difficulties by age two and were more likely to receive autism diagnoses,” Choi said.

According to Professor Nelson, even in the hands of a skilled clinician reliably diagnosing autism in children under two years of age is next to impossible. “April has convincingly shown that before the infant’s first birthday they are already showing early motor signs of the disorder,” he said. “If her work can be replicated with a larger sample size and perhaps in low-risk infants as well, it may pave the way for clinicians to identify infants who will develop autism before their first birthday.”

Choi recently received three fellowships from the Harvard University Centre on the Developing Child to further support the ground-breaking research. The fellowship is said to be unique because it brings together students from different disciplines for yearlong skill-building workshops and the chance to receive feedback on research from faculties cross the university.

Through the fellowship, Choi will build interdisciplinary thinking skills and translate her science-based research to a wide range of stakeholders, especially for children and families back home in Korea, where nearly one in 38 children is diagnosed with autism, which is one of the highest rates in the world.

University of Sydney PhD candidate, Olivia Karaolis, who worked with the Interdisciplinary Assessment Team for California Department of Disability Services, told F2L the findings are consistent with her experience.

“Around 12 months of age, we like to see children wave, ‘bye, bye’ or shake their head to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and pick up and point at things they want or like. Some little ones who are late in developing these skills can receive a diagnosis of an autism spectrum disorder later on. Does that mean that if the baby isn’t offering a toy at 12 months they have autism? No, because every child is different,” she said. “This research is going to be helpful in deciding when to start early intervention.”